Introduction

This is the twelfth post in a series on Victor Stenger's book God: The failed hypothesis. In his sixth chapter, The failures of revelation, Professor Stenger made a brief mention of Biblical archaeology, making the (rather common) claim that not only is there is no evidence for most of the Old Testament, but some parts of the Old Testament are directly contradicted by the archaeological evidence. My intention is to answer this criticism, or at least give hints as to how it might be answered.

The first post in this mini-series gave a general introduction to the topic of Old Testament archaeology as a whole. The subsequent posts will discuss individual periods and topics. This post will discuss the period of the Patriarchs, from Abraham through to Jacob, as described in the book of Genesis.

I am not going to claim that every question has been answered, or that there are not still areas of concern. There are two basic schools in "maximalist" archaeology (see the previous post in this series for what I mean by that term), those who favour a 13th century exodus and those who favour a 15th century exodus. My intention is to discuss both of them, although I favour the early exodus view. From what I have seen, both viewpoints have their strengths and weaknesses. In both cases, there are points which fit together nicely, and other points where things are less clear. The problem with archaeological evidence, particularly with regard to Israel/Canaan, is that there is never enough of it, and what we have doesn't always address the questions we want to ask, and it is often open to multiple interpretations. Certain key parts of the Biblical text are also open to multiple interpretations. The question of whether the archaeological record is consistent with the Biblical text is thus not as simple as many would claim, both those arguing for the accuracy of the Bible, and perhaps most particularly those who argue against it.

A few points from the introductory post are always worth bearing in mind. Archaeologists can only find what has been persevered (and currently only a small fraction of that has been dug up). Only a tiny fraction of ancient artefacts were left in the ground for us to dig up, and only a tiny fraction of those survived the centuries of decay and disturbance to be uncovered in the last few centuries of archaeological excavation. In particular, we have very little writing from Canaan itself. What little we have shows that society was literate; but there isn't enough to establish a history, as can be done in Egypt or Mesopotamia. You cannot therefore argue from an absence of evidence. Absence of evidence is what we expect, and we should consider ourselves lucky to have any evidence at all. Similarly, one should not expect to be able to prove the existence of Abraham from the Archaeological record. The Christian believes in Abraham because of the testimony of Christ, who Christians understand to be divine and thus infallible. There is, of, course, circumstantial evidence to support these beliefs, and evidence to support the incarnation. The question is can the atheists, or other critics of Christianity, Judaism, and (to a lesser extent) Islam disprove the Biblical account?

The second point I made which is worth repeating is that there is a difference between the data and the interpretation of the data. There are numerous different interpretations which can be made. The burden on the atheist is not just to show that one particular interpretation of the archaeological data conflicts with one particular interpretation of the Biblical data, but that all possible interpretations of the archaeological data conflict with all interpretations of the Old Testament. In particular, there is a matter of chronology. As noted in my introductory post, proposed dates for Abraham's journey into Canaan range from about 2050 to about 1700BC. That is a great deal of uncertainty, and the sceptic needs to consider all those periods. He can't just find evidence against Abraham at, say, 1850BC and say that he has settled the case.

So what evidence do we expect Abraham, Lot, Isaac and Jacob to leave behind? The answer is, for the most part, not very much. They were not people of especial importance in their society. They were, of course, of huge importance to the Biblical history, but that is a different issue. Abraham was, for example, a Bedouin tribal chief. His household and servants numbered a few hundred people. He was rich, and had dealings with many of the people in the local cities and even with the Egyptians. But he was just one of many people of similar stature. In Genesis, we find mention of Mamre, Eschol, Abner and Moreh, people who, it could be argued (though not with certainty), lead a similar lifestyle to Abraham. We find mention of people like Abraham in the Mesopotamian and Egyptian texts, but no mention of names. There is, it would appear, no particular reason why he would have been singled out for mention in the surviving Egyptian monuments (which existed to praise the Pharaohs and other high ranking officials). He left behind no permanent structures in the land except his tomb. He did not live in any cities. He and his followers doubtless left behind some shards of broken pottery, but there would be nothing stamped on it saying "This belonged to Abraham." To the archaeologist, even if it was found, it would be nothing except generic Middle Bronze age pottery.

Thirdly, I am not an archaeologist, but merely someone with an amateur interest in the subject. There is an old adage that you venture outside your area of expertise, and this exercise is a good illustration as to why. Before starting out, I thought that I had a decent grasp of the material. After checking my sources, and trying to corroborate them, I realised that it wasn't anything like decent enough. Most importantly, I don't have the resources that a professional would have. Too many times I have tried to check something, and I have found that the sources I do have don't go into enough detail to answer the specific question that I had. So what I am presenting is something of a best effort, and I would welcome corrections.

I should start by giving an overview of the Biblical account. Abraham (or Abram) was born and raised in "Ur of the Chaldeans", which most likely refers to the well known city of Ur in Southern Mesopotamia. At some point, he accompanied his father and brothers, as they journeyed up the rivers to Haran (or Harran), close to the modern border between Turkey and Syria. After the death of his father, Abraham, with his wife Sarah (or Sarai) and nephew Lot and various servants, travelled from Haran to the land of Canaan, modern Israel. Abraham was without child, and, despite being elderly at this time, trusted in God's promise that he would become the father of many nations. Shortly after arriving in Canaan, Abraham was driven to Egypt due to a famine. In Egypt, he became very wealthy, gaining many slaves and camels, and returned to Canaan. He parted with Lot, because of the number of their flocks, and Lot went to settle in the region of the Dead Sea, around the cities of Sodom and Gomorrah. Abraham continued to live as a Bedouin in the Southern part of Israel and the Negev. There was a war between some Kings of Mesopotamia, lead by Cheodorloamer of Elam, and the King of Sodom and neighbouring cities; the Mesopotamian Kings defeated the valley cities, but on their way back home were ambushed by Abraham, who rescued Lot. Abraham's desire for a child, and his wife's inability to bear one, led her to loan him her slave girl Hagar. From that union, Ishmael was born. However, God was not pleased, and reaffirmed that it would be through Sarah that Abraham's heir would come. God then destroyed Sodom and the surrounding cities as a punishment for their great evil, although Lot was spared. After some disputes with the Philistines at Gerar, Abraham returned to his tents near Hebron, where his son Isaac was born, the fulfilment, twenty five years later, of God's original promise to Abraham when Abraham entered Canaan. Sarah's jealousy with Hagar came to its fullness, and she drove Hagar and Ishmael away. Abraham was then tested by God, who asked Abraham to sacrifice Isaac, the child that God had promised would be the heir of Abraham and father of the nation that would be born from Abraham. At the last moment, God told Abraham to spare his son's life, and a ram was offered in Isaac's place. Many years later, Sarah died, and was buried in some land which Abraham purchased near Hebron. Abraham arranged a wife for his son from among his relatives still living in Haran. Abraham remarried and had other children, who would be the ancestors of many of the desert tribes to the South of Israel. Later on, Abraham died, and was buried alongside his wife by Isaac and Ishmael.

Isaac and his wife Rebekah had a generally peaceful life, aside from some further disputes with the Philistines at Gerar, which were resolved peacefully. Rebekah gave birth to twins, Esau the first born, and then Jacob. Neither were of particularly good character. Esau, haughty and proud, married local women who abused their mother-in-law. Jacob cheated his brother out of his inheritance rights as the first born, and then his father's blessing. This enraged Esau, and Jacob's mother sent him away to Haran, ostensibly to find a wife. On his way, Jacob encountered God at Bethel, an experience which changed him. Arriving at Haran, he was soon smitten by his cousin Rachel, and asked to work for seven years in order to marry her. After the seven years, he was cheated out of his bride, and given the older sister Leah instead. Allowed to marry Rachel as well, the two sisters, aided by their slave girls, had a bit of a competition to see who could bear their husband the most sons. Eleven sons were born to Jacob in Haran. After twenty years in Haran, Jacob left to return to Canaan and the land where he has born and raised, with his wives, sons, servants and by now numerous flocks. He encountered God again as he was about to re-enter Canaan, and was given the new name of Israel. He survived a nervous encounter with Esau, and settled down near Shechem. A dispute between Jacob's sons and the inhabitants of Shechem led the family to move away to the South. A twelfth son, Benjamin, was born to him in Canaan, but his favoured wife Rachel died in childbirth. Benjamin's full brother was Joseph. Israel favoured Joseph and Benjamin above their brothers.

The key texts that are often used to establish the chronology are 1 Kings 6:1, Exodus 12:40, Genesis 47:9, and Genesis 25:26. 1 Kings 6:1 states that there were 480 years between the construction of Solomon's temple and the Exodus. The construction of Solomon's temple is usually and reasonably uncontroversially dated (to with a few years) to 967BC, based on comparing the data in the books of Kings and Chronicles with the Assyrian records. Exodus 12:40 states that the Israelites were in Egypt for 430 years. Genesis 47:9 states that Jacob was 130 years old when he came into Egypt. Genesis 25:26 states that Isaac was 60 years old when Jacob and Esau were born. If we add all these numbers up, then we get a date of 2057BC for the birth of Isaac, with Abraham entering Canaan some 25 years earlier. This would place Abraham towards the end of the MB1 (sometimes called, including in several of my sources, Intermediate Bronze Age or EB4, since after it was first named as MB1, the pottery types are closer to those from the early bronze age than later middle bronze age pottery) archaeological period.

The problem is that each of these numbers are disputed. Firstly, all these numbers are likely to be rounded, so even if we take them at face value there is going to be a few years, or even a few decades, imprecision. The 480 years of 1 Kings 6:1 is not the only Biblical date of the Exodus. One can add up the periods of the Judges, which, even not including a few unrecorded or distorted time periods, gives a length of time that significantly exceeds 480 years. A naive reading of the Judges data would put the Exodus in the 16th rather than 15th century. Most people, however, argue that several of the judges overlapped, which is not unreasonable. Secondly, large numbers such as 480 were often used in the ancient world as symbolic rather than literal, with 40 years used to indicate a long passage of time rather than to be interpreted as a literal figure. On the other hand, Exodus 1:11 states that the Israelites built the city of Ramesses, which, if taken literally, would indicate a 13th century Exodus, about 200 years or so later than the early exodus date. This is probably the most commonly accepted date for the Exodus. All critics of the historicity of the Exodus that I have seen use this date, as well as numerous notable defenders of the Biblical account. There is also a textual variation in this verse, with some sources reading 440 years. There is a textual variation around the 430 years of the time spent in Egypt, with some sources (most notably the Greek translation) saying that was the time spent by the ancestors of the Israelites in both Egypt and Canaan. So if you take this reading plus a 1260BC date of the Exodus, Abraham would enter Canaan at about 1690BC, with Isaac born in 1665BC, towards the end of the MB2 archaeological period. Plus I have seen others question the long ages of the Patriarchs, suggesting that these are textual corruptions. And, of course, these are the two most extreme cases, with numerous other possibilities between them.

I am not going to stick to an exact chronology in these posts, call it Biblical, and demand that everyone follows it. Instead, I intend to compare the Biblical narrative against what we know from extra Biblical history, and judge from that the possible times when everything might be as near consistent as possible. I am not going to get hung up over precise dates, but instead use the various interpretations of the Biblical chronology as a general guideline for which time periods to consider.

So anyone searching for evidence that either proves or disproves the existence of Abraham, his son and grandson from archaeological data (if it were possible) is going to have to search over a large range of times, from about 2060BC through to about 1660BC for the birth of Isaac, with the other events dated accordingly.

Biblical maximalists do not seek to prove the Patriarchal narratives from the archaeological record. They have other reasons for accepting the Biblical text; and we cannot and should not expect to find historical proof of the narratives in the ground, simply because so little survives to our day, and the evidence that does survive is not in general the sort of thing which would confirm the detailed stories. Maximalists are still interested in the archaeological picture, but, aside from their use in refuting the claims of minimalists, this is primarily to get a better idea of the historical context and interpretation of the accounts. Biblical minimalists, on the other hand, do seek to prove the narratives false; that is to find inconsistencies between the accounts in Genesis and what we know about the Middle Bronze Age from historical sources. So the focus of any investigation should be to whether or not the narratives conflict with secular history, and if so to what extent, and is there any chance that the difficulties could be resolved?

The criticisms

So, having described the Biblical picture, it is worth looking at how Professor Stenger responds to it. All he does is state that Abraham is likely a mythological figure, with a reference to Finkelstein and Silberman's book The Bible Unearthed. So what does Professor Finkelstein have to say?

First of all, he comments that the Biblical account seems plausible because the accounts of the Patriarchs are in reasonable agreement with the modern Bedouin lifestyle. Mentions of Ur and Harran also ring true and give the accounts an air of historicity. Various elements such as personal names, marriage customs, and land purchase laws were in accord with records from the general time period.

However, he finds problems. Firstly, the Biblical chronology is difficult to establish, and particularly the long lives of the Patriarchs and differences in the lengths of the genealogies listed at the time of the Exodus cast doubt on it. The search for the Patriarchs was ultimately unsuccessful, because none of the periods were completely compatible with the Biblical stories. The Western migration of Amorites from Mesopotamia to Canaan, which Albright correlated with Abraham's journey, was illusionary, since in practice the Amorites started in Syria and Canaan and went East into Mesopotamia. The cultural parallels found could apply to almost any culture in the ancient near East, and so don't prove anything.

In the Early Bronze Age, Canaan was dominated by large, well fortified cities; this is different from the picture of the Genesis account. However, as the EBA came towards its end, this system collapsed. The cities were destroyed and became ruins, many to never recover. The culture of the next few centuries -- late EBA though to early MB2 -- was marked by a culture with few large cities. Most of the population practised a pastoral nomadic lifestyle. Albright believed that he had identified the time of the Patriarchs within this window. He identified the destruction of the cities with a Western invasion of the Amorites, known from the Mesopotamian texts. He also identified Abraham as part of this migration.

However, this picture did not survive future investigation. The EBA civilisation did not disappear overnight, but was marked by a more gradual decay. The Amorites did not originate in Mesopotamia and move to the Levant. They originated in the Levant, and moved to Mesopotamia, the opposite direction to Abraham. Equally, MB1 was not a completely nomadic period: the majority of the population lived in smaller towns and cities. The population was not invaders, marked by a different pottery style, but the descendants of their EBA ancestors. Equally, some sites, such as Shechem, Hebron and Beersheba were not populated in the MB1 period.

The next proposal to place the Patriarchs was to put them in the MB2 period. This Finkelstein also rejects. The MB2 period was one of advanced urban life. Canaan was dominated by large and powerful city states, such as Hazor, Gezer and Megiddo. These cities are not mentioned in the Biblical text. The names of the Patriarch narratives are not just limited to this era -- Jacob, for example, is common in the Middle Bronze age, but also Late Bronze and other periods. The cultural practices of the Nuzi texts were common across a wide range of time periods, not just the MBA.

Finkelstein instead finds correlations between the Patriarchal narratives and the Iron Age, but since this is not really relevant to the discussion of whether the accounts are true (which depends on whether or not there are correlations in the Middle Bronze Age or towards the end of the Early Bronze Age), I won't discuss it.

There are (Finkelstein and Silberman claim) various anachronisms in the text, which place it's composition during the period of the monarchy.

- The repeated mentions of camels is inconsistent with the observation that the earliest evidence for camel domestication in Canaan is from the tenth century BC.

- The goods carried by the camels matched the Arabian trade of the neo-Assyrian period.

- The Philistines first appear in the Archaeological record as one of a group of sea peoples at about 1200BC. Gerar was an unimportant village at the start of the Iron Age (when the Philistines arrived), and only became important during the neo-Assyrian period.

- The Arameans are not mentioned as a distinct ethnic group until about 1100BC. Ammon, Moab and Edom, whose origins are discussed in the book of Genesis, were the significant rivals of Israel and Judah during the Kingdom period. In particular, Edom was not mentioned as a major power until the 8th century BC.

- The tribes that Genesis states were descended from Ishmael are also only recorded in late Assyrian and Babylonian texts.

- Other places mentioned in the stories also don't match the Patriarchal period, but do fit the Iron Age when Finkelstein supposes that the accounts were composed.

- The one place which can be identified with certainty in Chedorloamer's raid against Sodom is Kadesh, which was also predominantly occupied during the seventh and eighth centuries.

- Harran was also a well known neo-Assyrian city.

- The account of Abraham is linked to Judah, and in particular the royal cities of Hebron and Jerusalem. The account of Jacob is associated with Northern Israel. This suggests that the redactor of the text took two separate legendary national heroes, one for Israel, and the other Judah, and merged them together into one family. Abraham also built altars at the important Israelite sites of Shechem and Bethel, which was due to the writer from Judah trying to incorporate his Northern cousins into his text and make Abraham a unifier of the Northern and Southern traditions.

Since all of these details fit the seventh and eighth century, that suggests to Finkelstein that the accounts were written at those times.

Of course, Finkelstein's account is not the only one available. So it is worth seeing what responses can and have been made to it.

The broader archaeological picture

The first thing to note is that, according to the Biblical Chronology, the period of the Patriarchs lasted over two hundred years. This is a long time, and plenty of time for different cultural milieus to come and go. There is no reason, then, for us to restrict our search to just one archaeological period, and try to fit all of the Genesis narratives into it. For example, the account of Abraham doesn't mention large cities, except Gerar. This fits in nicely with the late early bronze period or MB1 periods as described by Finkelstein (and others). During the MB2 period, there was a gradual transition to a more urban life. At the start of MB2, the MB2a period, we see towns and cities start to spring up, though often unfortified. The twelfth dynasty Egyptian excretion texts seem to indicate that a sedentary and nomadic population existed alongside each other. In MB2b, the cities became larger and well fortified, and the process of urbanisation was completed. In the book of Genesis, we find that by the time that Jacob had returned to Canaan, he does have the tension of trying to lead a nomadic lifestyle while cities are becoming more important, as seen, for example, in the accounts of Genesis 34 and 35. Equally, we should be wary of arguments of silence. Finkelstein asked, for example, why there was no mention of Hazor or Megiddo in the Genesis narrative. The answer is why should there be? Hazor was to the North of the Land, and controlled the area that would later be known as Galilee. Megiddo was the major city in the Jezreel valley. But the Biblical text puts Abraham, Isaac and Jacob in the central and Southern hill country; from Shechem down to Beersheba and the Southern desert. The obvious reason why Hazor is not mentioned because the Patriarchs didn't live in the part of the country it controlled.

First of all, we need to narrow down the dates of the Patriarchs a bit. The place I will start is to ask when the various sites mentioned in the accounts are occupied. If we can find a coherent picture, then that will firstly give some testimony to the veracity to accounts, and secondly narrow down the time period. I was intending to base this on a paper by John Bimson, Archaeological Data and the Dating of the Patriarchs. However, while I think that methodology used by Bimson is reasonable, and its conclusions might still stand up, the paper has a number of limitations. Firstly, it is now rather old and outdated; for various sites Bimson relied on a surface survey, but they have now been excavated so there is better data. Secondly, Bimson just distinguishes between MB1 and MB2. In practice, the MB2 period lasted for several centuries, and archaeologists distinguish between early and late MB2, or MB2a and MB2b. Several sites, which Bimson's proposed chronology would need to be populated in MB2a in fact date to MB2b, a few centuries later. I have supplemented my work with whatever other data I can find. My main source is the rather mixed Archaeological Encyclopedia of the Holy Land (a great reference for some sites, but its treatments of others is rather too cursory), and backed it up with whatever excavation reports and other information I have been able to access. But, again, I should note that I am not an archaeologist, don't have access to the best sources, and would welcome correction.

The first thing to do is to list the sites which appear in the Abraham, Isaac and Jacob narratives. This I do in the table below. The Patriarchs, with the exception of Lot, did not live in established towns. They were nomadic, dwelling in tents. They had a large number of servants, and a great deal of livestock, and as such they would have presumably preferred to live in an area where there was no established settled population. The land around the towns would be taken over for agriculture and grazing for the animals which belonged to the people living there. If Abraham, Isaac or Jacob had lived too close to a town, then there would have been competition between them and the local inhabitants (as indeed happened between Jacob's family and the inhabitants of Shechem, or Isaac and the inhabitants of Gerar). So we should not expect everywhere mentioned in the narratives to be inhabited at the time of the Patriarch in question. Some places clearly would not have been inhabited (at least by a settled population) at that time. For example, Beersheba is mentioned as a group of wells which were disputed between the Patriarchs and the Philistines of Gerar. If there was a town there at the time, those wells would have been essential as its water source. It is hardly likely that its inhabitants would have stood by while two groups of foreigners quarrelled over which one of them owned it. Thus the natural reading of the Biblical text is that Beersheba did not have a permanent settlement at the time of Abraham and Isaac. Similarly, Genesis 12:6 records that Abraham built an altar at Shechem: the first thing he did when he came to Canaan. This does not require that there was an inhabited city there at the time. Indeed, if there was, then the inhabitants would probably not be very happy about this foreigner barging into their city and building an altar to a God they didn't know. Now, the altar might have simply been near Shechem; maybe Shechem was uninhabited at the time, just the remains of an earlier abandoned city; maybe I have misinterpreted the passage. But the reference in the text does not necessarily indicate an inhabited city. The asterisks in the table mean that although the site is mentioned it is not clear that there is a town there (for example, it could just be an altar, well, heap of stones or encampment). The (X) means that it there was likely no permanent settlement, at least as I read the text. The (?) means that either the site hasn't been identified clearly, or it hasn't been excavated. If anyone has better information of the occupation levels of the sites, I would be delighted to hear it.

| Abraham | Isaac | Jacob | MB1 Occupation | MB2a Occupation | MB2b Occupation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Damascus | ? | Yes | Yes | ||

| Shechem (*) | Shechem | A few shards | Yes | Yes | |

| Bethel (*) | Bethel (*) | A few houses | A few houses | Yes | |

| Ai (*) | No | No | No | ||

| Zoar | ? | ? | ? | ||

| Sodom | ? | ? | ? | ||

| Gomorrah | ? | ? | ? | ||

| Admah | ? | ? | ? | ||

| Zeboiim | ? | ? | ? | ||

| Ashteroth-karnaim | ? | Yes | ? | ||

| Ham | ? | ? | ? | ||

| Shaveh-Kiriathaim | ? | ? | ? | ||

| Salem | ? | ? | Yes | ||

| Hebron (*) | Hebron | Hebron | A few shards, burials | Yes | Yes |

| Oaks of Mamre (X) | A few shards | ? | ? | ||

| Kadesh | Yes | No | No | ||

| Hazazon-tamar | ? | ? | ? | ||

| Shur (*) | ? | ? | ? | ||

| Dan | Yes | Yes | Yes | ||

| Beer-lahai-roi (*) | Beer-lahai-roi (*) | ? | ? | ? | |

| Gerar (Tell Haror?) | Gerar | No | No | Yes | |

| Beersheba (X) | Beersheba (X) | No | No | No | |

| The Negev | Yes | No | No | ||

| Galeed (*) | ? | ? | ? | ||

| Peniel (*) | ? | ? | ? | ||

| Succoth (X) | No | A few shards | Yes | ||

| Bethlehem (*) | ? | ? | ? | ||

| Eder (*) | ? | ? | ? | ||

| Dothan (*) | No | ? | Yes | ||

| Timnah | ? | ? | ? | ||

| Chezib | ? | ? | ? |

Many of these sites are difficult to assess. I will discuss Sodom, Gomorrah, Admag, Zoar and Zeboiim below. The exact locations of Ham, Shaveh-Kiriathaim, Galeed/Mizpah, Peniel/Penuel, Beer-lahai-roi, the Tower of Eder and Timnah are unknown, except that the first four evidently lay in Transjordan. Other sites, as indicated, do not require an inhabited site.

Damascus is difficult to excavate because of the modern city on the site, and I haven't been able to find any archaeological information. The city is mentioned in records from 12th dynasty Egypt and the Mari tablets, which correspond to the MB2 period. In Genesis, Damascus is the place where Abraham's original adopted heir was from.

Shechem was populated from the start of the MB2 period. The city was established at about 1900BC as an unwalled settlement, but by the end of MBII at around 1650BC this had turned into a significant fortified city. Occupation during MB1 is less clear, and the consensus seems to be that it wasn't occupied, with just a few scattered shards found. However, the reference to Shechem in Genesis 12 doesn't necessarily indicate a settlement. Abraham camped by an oak tree, which was indicated as being located near Shechem; so the name is used as a reference so readers could identify the place rather than specifying a town. It was clearly an established city by the time of Jacob in Genesis 34, although the text doesn't mention that it was fortified, and the ease by which Jacob's sons were able to enter and plunder the city might suggest that it wasn't. Shechem is also mentioned in Egyptian texts of the 12th Dynasty, around the time of Sesostris III (including regarding a military campaign against it in roughly 1860BC).

Bethel is usually associated with Beitin, which is what I have assumed when filling in the table. A few researchers have suggested that it should be at Bireh instead, although this is heavily disputed. In Genesis 12, Abraham established an altar near Bethel, and he had an encampment there in Genesis 13. This doesn't require that there was an established town at the site. Bethel is mentioned again in the Jacob account of Genesis 28:19, set at least 125 years later (according to the internal chronology of Genesis). The text here is ambiguous, stating that "He called the name of that place Bethel, but the name of the city was Luz at the first," and that he turned aside to stop there (suggesting a city), but he slept in the open using a stone as a pillow, suggesting it was more of a ruin. Jacob returned to Bethel in Genesis 35 (at least twenty years later still), and settled there for a while. None of these references require a large fortified city, but the Jacob narrative in particular suggests that there was at least a small settlement (and perhaps more). Archaeological excavations have found an early bronze settlement, and traces of a few houses and a hilltop altar from the end of MB1. This continued into MB2a (perhaps even the occupation of the site decreased slightly). A major fortified city was established in the MB2b period.

Ai is traditionally associated with et-Tell, although its location doesn't precisely match the detailed Biblical geographical description in the books of Joshua and Genesis, and it was only occupied in the Early Bronze and Iron Ages. A better possibility for the Ai of Abraham through to Joshua's day (which I have used in the table above) is the nearby site of Khirbet el-Maqatir, which shows occupation from the Middle Bronze III period to a destruction in the Late Bronze I period. It is also possible that the city jumped from one site to another, so et-Tell was Iron Age Ai, and Khirbet el-Maqatir Middle and Late Bronze Age Ai. The Abraham narrative states that he pitched his tent on a hill between Bethel and Ai. This doesn't necessarily indicate that the city was occupied at that time. The site is also fairly shallow, with exposed bedrock, so occupation layers might have been disturbed by later development.

The location of Ashteroth-karnaim is unclear. It is mentioned in Genesis 14 as one of the cities taken by Chedorlaomer and his allies on his way to Sodom. It is not even clear whether it refers to one or two cities. The two main proposals (Tell Ashtarah and Sheikh Sa'ad) both show occupation levels from the Early Bronze age to the MB1 period. (At least this is what was claimed by Bimson, but Bimson uses some old sources; I haven't been able to verify this information. It is likely to be from a surface survey). Ashteroth also has a probable mention in 12th Dynasty Egyptian Execration texts, corresponding to the MB2a period.

If Salem represents Jerusalem ("The City of Salem"), as is, then there is clear evidence of MB2b occupation. The city is also mentioned in Egyptian texts of the period. There is little sign of MB1 occupation. However, it should be borne in mind that Jerusalem is a presently occupied city, and therefore large parts of the city have not been properly excavated. For example, there have also been few LB IIa remains found in the city, even though we know that Jerusalem was an important city at the time because its King corresponded with the Egyptian Pharaoh Akhenaten. The Biblical reference is to Melchizedek, King of Salem and Priest of God Most High, which indicates that the site should be occupied, but might not require more than an unwalled town and ritualistic site. It should also be noted that Abraham's visit to Mount Moriah to sacrifice Isaac makes no mention of a city nearby, even though ancient Jerusalem was located on the ridge to the South of Mount Moriah. If Salem should not be associated with Jerusalem, then its site is unknown.

Hebron in the main Abrahamic account is associated with the Oaks of Mamre, which suggests that the place was more an encampment than a permanent settlement during the early part of Abraham's time of the land. An alternative is that Mamre is an area a little bit outside the city. However, towards the end of Abraham's life, some sixty years or so after he entered the land and over forty years after Abraham's alliance with Mamre, he purchased a burial site from the Hittites who dwelt in Hebron, which was by then a walled city. This might suggest that Hebron was founded during the latter part of Abraham's life. Hebron itself shows extensive MB2 occupation. The city seems to have been established sometime in the MB2a period, and in particular extensive fortifications have been found dating to the MB2b period. There are a few tombs nearby with MB1 pottery, but no sign of any permanent settlement. This is consistent with there being a nearby encampment in the MB1 period, with the permanent settlement growing from that site into a walled town by the end of MB2. Numbers 13:22 suggests that Hebron was established at about the same time as Tanis in Egypt. Although the city of Tanis grew into prominence in the late New Kingdom and especially the Third Intermediate period, much later than the time of Abraham, there are remains found from the Old and Middle Kingdoms. The earliest inscribed remains are related to a temple founded by Amenemhat I (about 1991-1962 or 1979-1950BC), although the city might have been founded a little earlier during the later part of the 11th dynasty. This corresponds well with a MB2a date for the founding of Hebron. However, there is no indication that I am aware of that the MB2a city was fortified, as suggested in the account where Abraham purchases the burial cave.

Kadesh is located near an Oasis in the Negev desert. There are two proposed sites, Am Qudeis and Am el Qudeirat. Surveys have found extensive MB1 pottery near Am el Qudeirat (though, as far as I can find, not at the Tell itself), but no MB2 pottery. Rather than a large city, as far as I can tell (and I haven't been able to discover much information beyond what I have just written) this MB1 occupation seems to have been scattered over a number of small villages in the valley. The reference to Kadesh in Genesis 14:7 doesn't necessarily require any more than this. It describes the coalition of the kings coming to Kadesh and defeating the country of the Amalekites rather than a definite city. The other references to Kadesh in Genesis 16 and 20 just use it as a geographical marker rather than indicating a sedentary occupation. It is also possible that the Kadesh of Abraham's day was elsewhere.

Hazazon-tamar is another of the cities attacked by Chedorloamer and his allies. 2 Chronicles 20 links it with the oasis of En Gedi, but no Bronze age remains have been found there. However, the excavations around the oasis haven't been especially extensive.

Dan is mentioned (under the older name of Laish) in Egyptian texts of the 12th Dynasty. The site is also mentioned in the Mari tablets. There have been extensive MB2 finds at the site, including an impressive arched gate. There is less from the MB1 period (stratum XIII), but some pottery has been found suggesting that there was a small settlement at the site. The mention in Genesis 14 doesn't require any more than that.

Gerar is the home of Ambilech the Philistine in the Abraham and Isaac accounts. It is the only city in Canaan which Abraham interacts with (aside from the brief mention of Salem), until his dealings in Hebron late in his life. Isaac lived in Gerar for a while, before being forced out, after which he first of all to the valley of the river Gerar (where there was evidently very fertile land), and then further afield to Beersheba. Gerar must therefore be located in this general vicinity, to the East or perhaps South East of Gaza. In each case Isaac came into conflict with the Philistines from Gerar. Thus Gerar exercised hegemony over a wide area, at least from the Gerar valley to Beersheba. It is notable that no other cities are mentioned in either the Isaac or Abraham accounts, which perhaps suggests (although this is a weak argument from silence) that Gerar was either the only or the most important city in the area at the time. It is also mentioned in Genesis 10:19 as being on the Southern border of Canaan, where it is associated with Gaza. The only other mention of the site in the Bible outside Genesis is in 2 Chronicles 14, where a Judean King pursues the invading Cushites to Gerar. In particular, the city is not mentioned in either the (fairly exhaustive) list of cities in Joshua, nor in the Amarna letters, perhaps suggesting that it was sparsely settled, if at all, in the Late Bronze Age.

Numerous cities sprung up around the Gerar valley in the MB2b period. The largest of these was Tel Haror, and this is most frequently identified with Gerar, although I haven't been able to find any definite evidence that confirms this assignment. In the table above I have assumed this identification. The only reason I have seen suggested for this identification is that assuming that this was the time period of Abraham, the Tel Haror, as the dominant city of the region, is the most obvious candidate for Gerar. Obviously, if Abraham was to be dated in a different time period, then this argument wouldn't stand up. The city was at its peak in the Middle Bronze age, although seems to have been in near-continuous occupation until the Iron Age. If Tel Haror is Biblical Gerar, then this would seem to rule out a MB1 and possibly MB2a Abraham, unless remains from these periods were missed by the excavators.

So are there any alternative sites which could fit an earlier date for Abraham? There are very few occupied sites in the region for either the MB1 or MB2a periods. The only options I have found on or near the Gerar valley are Tell el-Ajjul on coast (which doesn't really match the Biblical description), and Tell Beit Mirsam, which is on the border between the plain and the Judean hills, located about half way between Beersheba and Maresha, the site of the battle in 2 Chronicles, and a few miles from one of the sources of the Gerar river. Tell Beit Mirsam was one of the first sites to be scientifically excavated, by Albright in the 1930s, and as such plays an important role in the history of Biblical archaeology. I am not aware that it has been re-excavated since then, so the best information we have is from this rather early excavation. Albright found evidence of an Early Bronze Age settlement, and the site continued to be occupied during MBI. The city grew larger during MB2a, and was fortified in MB2b. The city then was at its height, and had contact with Hyksos Egypt. The city was destroyed at the end of the Middle Bronze Age, and abandoned for the first part of the Late Bronze Age. It was re-established in the second half of the Late Bronze age, and grew into a significant Iron age city. If we hypothesise an early date for Abraham, then this occupation history matches that of Biblical Gerar, and the site's location, while not as good as Tel Haror, is not inconsistent with the Biblical account. It also fits the Biblical account in that it was the only large settlement in the region of the upper Gerar valley and Beersheba during MB1 and MB2a periods. I am not aware that Tell Beit Mirsam has been identified with any other Biblical site. Albright's original claim that it was Debir has since been rejected. Thus Tell Beit Mirsam looks to me to be a reasonable candidate for Gerar if Abraham lived in the MB1 or MB2a periods -- it was occupied at the right times, it was the only city occupied in the region at the time, and it is within a day's walk of all the places associated with it in the Biblical account. However, I haven't seen this proposed by any archaeologists, and there is presumably a good reason for that.

If Gerar is to be identified with Tell Haror, or any of the other nearby MB2b sites, then this seems to be strong evidence against a MB1 or MB2a Abraham, unless there was a settlement on the site which was missed by the excavations. The other possibility for the early date of Abraham was that Gerar was at some other site, of which Tell Beit Mirsam looks to be the only real alternative. But note that randomly identifying Beit Mirsam with Gerar does not prove that the Gerar of Abraham and Isaac dates existed. All we have is that there was one settled city in or near the right part of the country at that time, consistent with the Biblical account. There is no other evidence providing the link; everything else is just speculation.

Beersheba has no settlement before the Iron Age. However, the Biblical account only refers to wells dug by Abraham and Isaac, and disputed between them and the Philistines at Gerah. This means that the Biblical testimony suggests that there wasn't a permanent settlement at the time of the Patriarchs, consistent with the archaeological data.

Abraham spent some time in the Negev desert, between Kadesh and Shur. This is, perhaps, surprising, since it is an arid region not really capable of supporting large flocks. For most of history, we don't find much evidence of occupation in the Negev. However, it is possible that varying climate would allow settlement in the Negev from time to time. A large number of MB1 settlements have been found in the Negev. Some of these are very small sites, just a few houses, while there were a few larger towns indicating a more settled population. There were no such settlements in the MB2 or EB3 periods. This suggests that during the MB1 period the climate in the Negev was such that it was possible to eke out a living there, while the lack of settlements during MB2 suggests (though certainly doesn't prove) that the land wasn't so suitable at that time. This makes MB1 the most likely period for Abraham's sojourn in the Negev, although we can't rule out later periods.

Succoth is usually associated with Tell Deir Alla, but this identification is uncertain. The Biblical account states that Jacob built a shelter for his livestock and house for himself at Succoth, giving the place its name, although he abandoned it shortly afterwards. This is consistent with the idea that there wasn't a pre-existing permanent settlement at the time of Jacob, although a later town took its name from his house. If the structure at the time of Jacob was just an animal shelter occupied for only a few years, it is possible that this was missed by the excavators. A little MB2A pottery was found in a surface scan of the site. The main occupation of the site seems to have begun in late MB2b or MB3. It is also possible that Succoth should be located elsewhere.

Bethlehem cannot be excavated because of the modern town on the site. The mention in Genesis account is that Jacob's wife Rachel died on the road to Bethlehem, so it is not even clear that it was an occupied town at the time.

Excavations at Tel Dothan have revealed a MB2 town, but no MB1 occupation. I haven't been able to determine when in MB2 it was occupied. The Biblical mention is merely that Joseph's brothers grazed their sheep near here, so doesn't require a large settlement.

At least, that is the situation, to the best of my knowledge. Bimson's original paper is obviously out of date, and I have tried to update it as well as I can. I am not an archaeologist, though, so don't have access to the best data. I would welcome corrections. The second problem is that it is not always clear whether the Biblical text's mention of a place represents a town, or something smaller such as an encampment, well or altar. For example, Genesis 13:18 reads "So Abram moved his tent and came and settled by the oaks of Mamre, which are at Hebron, and there he built an altar to the Lord." In the next chapter, we learn that Mamre is some sort of tribal chieftain, perhaps similar to Abraham. So is Hebron inhabited as a town at this time? Or is it just an encampment, which would leave little archaeological trace? If there was a town there, then how could Abraham have set up his tent? Why is it identified with some trees? The text states it is at Hebron rather than near Hebron. But, of course, Abraham's encampment could have been outside an existing town. However, by Genesis 23:10, Hebron was a walled town with its own gate, and a Hittite colony. So was Hebron built between Genesis 13 and Genesis 23? It is difficult to say just from the text. And there are a lot of places which are uncertain, either because they haven't been identified or because their location is uncertain. Equally, absence of pottery doesn't mean for certain that the site wasn't occupied at that time. The transition between MB1 and MB2 would have taken a few years, and occurred at different times in different places -- just a few decades difference, but that still could make a difference.

So what should we make of all this? Firstly, Jacob could not have been earlier than the MB2a period. The findings from Shechem in particular and Bethel confirm this. Additionally, in Egypt, the settlement of Asiatics at Avaris (across the river from Ramesses) began around the time of Sesostris III or Amenemhat III, towards the end of MB2a. The Israelites were not necessarily the first Semites to settle in Avaris, but they cannot have predated the settlement. The sites mentioned in Jacob's narrative otherwise match up well with the status of the sites in archaeology for MB2. The one exception might be Succoth, but the text doesn't indicate that there was a pre-existing town there at the time, only that Jacob built a house for himself and his (rather large) family, and a shelter for his animals, which might indicate that there wasn't an existing settlement at the site. In Jacob's time, the land does seem to be increasingly dominated by cities, more than was the case for Abraham. If my reading of the text is correct, and Bethel and Succoth weren't extensively occupied when Jacob visited them, then this would rule out a MB2b or later Jacob.

This means that the earliest we can place Abraham is towards the end of the MB1 period, although he too could have been later. The MB1 period is in general a good fit for the time of Abraham. As in the Biblical account, it was a time when there were few urban settlements, but the population was largely nomadic. MB2a wouldn't be too bad a fit in this regards, since the process of re-urbanisation didn't really get going until MB2b. The evidence from Kadesh and the Negev also supports an MB1 Abraham over an MB2 Abraham, although the evidence is not especially conclusive, since a nomadic MB2 Abraham might not leave many traces. If, as I believe, the Biblical account suggests that Shechem wasn't settled when Abraham built an altar there, then this would also suggest an MB1 Abraham. The problems with dating Abraham to MB1 are the sites of Gerar and Hebron. The only solution I can find for Gerar is to identify it with Tell Beit Mirsam, and identification which as far as I can tell hasn't been considered by any archaeologist, even those who support an MB1 date for Abraham (but I haven't really seen any of those discuss the problem of Gerar in detail). The early association of Abraham with Hebron doesn't require that there was a city there, and perhaps implies that there wasn't one, but towards the end of his life Hebron was a walled city. This certainly rules out the whole of Abraham's life being in MB1. It is possible that Abraham's long life spanned the transition between two archaeological periods, i.e. the early part of his life was in MB1 and the later part in MB2a, or the early part of his life was in MB2a and the latter part in MB2b. The first of these would require that Hebron was fortified in MB2a, but the archaeologists either missed it, or those fortifications were either destroyed to make way for the MB2b fortifications, or the MB2b walls were an extension of earlier MB2a walls.

Isaac has few sites associated with him. He settled in both Gerar and Hebron, which is fine if we can can find a solution for those sites for Abraham time, since whatever option we choose they would have continued to exist until Isaac's time. Beersheba wasn't occupied during the time of Isaac, but from the Biblical text we wouldn't expect it to be, since Isaac and the Philistines of Gerar were digging wells there to water their flocks, and fighting over them -- with no mention of a local town at the site.

The earliest we can place Abraham, based on the evidence surveyed so far, is with the early part of his life in MB1 and the latter part in MB2a. Even though this solution has a number of difficulties, in my view it remains the best match, based on the evidence from Kadesh, Shechem and the Negev, as well as the general cultural situation. This would date Isaac's birth to around 2000BC, give or take a few decades, Jacob's birth at about 1940BC, the Israelites settlement in Egypt at about 1810BC, and Abraham's birth at about 2100BC. These dates are obviously approximate, and a little bit later than the "Biblical" dates. I am dating it based on one particular date for the transition between the MB1 and MB2 archaeological periods, which is highly disputed (since there is no firm connection to Egyptian or Mesopotamian Chronology). This is roughly consistent with the early exodus and long Sojourn in Egypt Biblical chronology. The latest we could place Abraham (based on the fortifications at Hebron and the lack of urban culture described in the Genesis account) would be around the MB2a and MB2b transition, which would place the birth of Isaac at about 1800BC (or maybe a few decades later), and the other dates adjusted accordingly. This would be consistent with a late exodus chronology. A less good match would be to place Abraham entirely in MB2b.

So the situation for the Biblical conservative regarding site occupation isn't perfect. Whichever solution we go for, there are some anomalies. But neither is it a disaster; and the minimalists certainly can't claim victory. The anomalies are not deal breakers, and the Biblical account of few large urban sites and a largely nomadic population does seem to correspond well to the general archaeological picture for MB1 and MB2a. In general, the sites mentioned in the accounts were those occupied at the time, and the sites which the text implies did not have a sedentary population were not occupied.

So, with this analysis in hand, I will look at the remaining data to see how well it fits each of the options.

Haran

Haran is an important site for all three Patriarchs. Both Abraham and Jacob lived there for a time, and Rebecca, the wife of Isaac, originated from the city. The site of ancient Haran is not in dispute, being close to the modern Turkish village of Harran close to the Syrian border. The city was inhabited throughout the Middle Bronze Age. The city seemed to have links with the Third Dynasty of Ur, with a temple to the Sumerian moon god Sin established there which seems to be modelled after a similar temple to the same deity in Ur. This implies that there were some cultural links, and perhaps population movement, between the cities at about the time of Ur III, which corresponds to the late MB1 archaeological period. So, and early date for Abraham would place his migration during this period of cultural connection between Ur and Haran. But it is also possible that Abraham and his family moved in later. Thus, whenever we place Abraham, there are no inconsistencies between the Biblical account and the archaeological picture at the site.

Abraham in Egypt

Almost immediately after his arrival in Canaan, there was a famine in the land which caused Abram to emigrate to Egypt for a short time, before resettling in Canaan. This practice was not unusual, and similar migrations occurred through much of Egyptian history. The Nile river provided a constant source of water, while in the East people were more dependent on rainfall, which was not guaranteed. For example, we have records from the time of Ramesses II describing a group of people from Edom seeking entry into Egypt for precisely this purpose. But there were also times when Egypt was more closed to outsiders. So we can't use Abraham's brief settlement in Egypt as a means of confirming his date, but we can have a look and see if it is consistent with a general pattern.

The early chronology described above would place Abraham as being contemporary with the late eleventh dynasty. This was a period when Egypt was recovering from a time of turmoil. The Old Kingdom had split at the end of the 6th dynasty, and Egypt fell into a time of division, weak governance, and general lawlessness. Eventually, two stronger dynasties emerged; the 11th in Southern Egypt and the 10th in Northern Egypt. There was conflict between the two, and the 11th dynasty was victorious, with Mentuhotep II (about 2060 to about 2010 BC) uniting Northern and Southern Egypt. The early chronology would place Abraham's entry into Egypt around the time of this unification. The 11th dynasty didn't last very much longer after Mentuhotep II, with Amenemhat I usurping the Kingdom and forming the 12th dynasty at about 1990BC.

We have some literature describing the state of Egypt during this time, in addition to the tomb and temple inscriptions. In particular, I will cite a work entitled the "Prophecies of Neferty." This is set during the fourth dynasty, as a wise man outlines what will happen during the future, but the language of the piece is that of the Egyptian Middle Kingdom, and since it describes Amenemhat I as the Pharaoh who will restore order to Egypt, it us usually dated to the early 12th dynasty. It is looking back to the time before that, either the time of the first intermediate period, or the years immediately after reunification in the late 11th dynasty and before Amenemhat I came to rule. It might have been written to provide justification for Amenemhat I's rule and seizure of the throne and kingdom.

Among the problems described by this document, alongside a general break down of law and order, is that various foreigners came and settled in Egypt and became wealthy at the expense of native Egyptians. The translation I'm using is by Vincent Tobin.

Foreign birds will breed in the Delta marshes, having made their nests beside the people, for men have let them approach through laxness.

All joy has been driven out, and the land is plunged into anguish. By those voracious Asiatics who rove throughout the land. Foes have appeared in the east. Asiatics have entered Egypt. We have no (border) fortress, for foreigners now hold it, and there is no one to heed who the plunderers are.

Desert beasts will drink at the river of Egypt. They will rest on its shores, for there will be no one to frighten them.

Every mouth is full of "Take pity on me," but all goodness has been driven away. The land perishes, for its fate has been ordained. Its produce has been laid water. And its harvest made desolate. All that has been accomplished is now undone. A man's property is taken away, and given to one who is a stranger. I shall show you a nobleman with nothing, a foreigner prosperous. The one who was slothful now is filled, But he who was diligent has nothing.

The land is destitute, though its rulers are numerous. It is ruined, but its taxes are immense. Sparse is the grain, but great is the measure, for it is distributed as if it were abundant.

So what we learn from this passage is that Egypt didn't have control of its borders. Some barbarians (the term is a generic one meaning people from from the North East, from Syria, Canaan and places like Moab, Edom and Midian) had evidently just come to plunder and rob. Others settled down by the river, and grew prosperous. Rulers were corrupt, and resources were distributed, including to the foreigners, even though the average Egyptian was destitute. So the idea of Abraham entering Egypt with his household during this time, either late in the first intermediate period, or in the early Middle Kingdom before it had become stabilised by the twelfth dynasty, as a moderately wealthy man and leaving it as an exceptionally wealthy man is certainly plausible. If the border fortresses were unmanned, there would be little to stop him coming in, and if the people lax in letting foreigners settle down and the rulers corrupt, then he could well become enamoured of one of them, and gain. So while these passages probably do not describe Abraham in person, they describe a similar culture to that which Abraham is described as experiencing in Genesis 12. This situation changed dramatically soon afterwards: Amenemhat I built a series of forts and walls to protect the North Eastern border.

Another example to cite is the tale of Sinuhe. This is a twelfth dynasty story about a man who was an official under Amenemhat I. When that king was assassinated, he fled Egypt into Syria, where he lived for a while, had numerous adventures, and eventually realised the worth of a good Egyptian burial and returned to his homeland. The story is a work of fiction from the Middle Kingdom, but still will reflect the general culture of the time.

Shortly after leaving Egypt, Sinuhe encounters a Bedouin chieftain:

I alighted at the Island of Kem-wer. Thirst overcame me, and it hastened me on; I was parched, my throat dry. And I said: This is the taste of death. But I raised up my heart and gathered together my limbs. I heard the sound of the lowing of cattle, and I looked upon Asiatics. Their Bedouin chief recognised me, a man who had been in Egypt. He gave me water and boiled milk for me, and I went with him to his tribe, and what they did for me was good.

After this brief stop, Sinuhe resumed his journey North. This chief, if he existed (and this is a work of fiction), would have been a contemporary of Abraham if my preferred option for the chronology is correct. Similar to Abraham, this chief had been to Egypt and associated with the royal court since he had previously met Sinuhe. He had returned from Egypt, and lived either in the region of the Negev or Northern Sinai. What it tells us is that the story that someone like Abraham lived in Egypt for a short period and was associated with the Pharaoh's court was believable to people at the time, since a similar thing happened to this Bedouin chieftain.

Finally, I should mention the tomb painting at Beni-Hasan depicting a Asiatic caravan visiting an Egyptian official.

This painting is taken from the tomb of a Khnumhotep, an Egyptian official who lived later in the twelfth dynasty during the time of Sesostris II and Sesostris III, around the time when we would place Joseph on the early chronology, and close to the time of Abraham on the late chronology. Again, there is nothing to connect this caravan to the Midianites traders who sold Joseph into Egypt, but it depicts similar people at a similar time. There is nothing earth shattering about this: traders visited Egypt throughout Egyptian history, but it is still confirmation that the Biblical narrative matches contemporary practice. The robes of the depicted Asiatics also resemble the dress of the Israelites as described in the Bible.

The late chronology would place Abraham as being a contemporary of the latter part of the twelfth dynasty, or perhaps the early thirteenth dynasty. Archaeological investigations have shown that there was a growing population of Asiatic Semites living in the Egyptian delta at this time. Abraham and his household would have fit in alongside these.

The general cultural context

So now we come to the general cultural context for the Patriarchs. We have a large number of tablets from Mesopotamia from the general period of the Patriarchs, describing common life at the time. The most relevant of these are probably the Mari tablets at around 1800-1750BC, just after the Patriarchal period by my the early date, or at the height of it if we accept the later date. The Nuzi tablets from the fifteenth century are a bit later, but also describe a similar culture. We also have numerous records from the Old Babylonian period, particularly in the law codes.

These tablets also describe many of the customs we see in the Genesis accounts. For example,

- In Genesis 15:2, it is recorded that Abraham had adopted a servant from Damascus as his heir. This practice is recorded in various tablets from Mari and Babylon.

- Both Abraham and Jacob, when their wives were barren, took one of their wife's maidservants to produce an heir. This was an acceptable practice at the time, and is documented in Kanesh, the Hammurabi law code, and in the Nuzi documents.

- The inheritance laws show the practice of giving extra rights to the first born. While Lipit Ishtar of the Isin dynasty decreed equal inheritance, the Hammurabi law code and Mari tablets give double inheritance rights to the firstborn (as seen in the Mosaic Law code, Deuteronomy 21:17). Later, the Neo-Babylonian law code gave two thirds of the inheritance to the first born son. In the Genesis narrative, Sarah sent away Ishmael so that he wouldn't receive equal inheritance with her son (Genesis 21:10). Under the Lipit Ishtar law code, a slave woman's children were not granted an inheritance if the slave-woman was freed. Two generations later, and we see Jacob and Esau fighting over the first born inheritance rights. Lipit Ishtar again stated that inheritance should be reserved to the sons of his main wife. This was Abraham's practice, giving all he had to Isaac, and leaving his later sons by Keturah (Genesis 25). Thus the inheritance practices of Abraham match those of the earlier Isin dynasty, while two generations later the practice seems to be more consistent with Mari and the Old Babylonian law code.

- Jacob could not divorce his less favoured wife Leah; this is paralleled in the Lipit Ishtar law codes.

- Some Nuzi tablets, called "tablets of sistership", were agreements where a man adopted a woman as a sister. A wife enjoyed both greater protection and a superior position when she also had the legal status of a sister. In such a case, two separate documents were drawn up, one for marriage and the other for sistership. This may explain why both Abraham (Genesis 12:10, 20:1) and Isaac (Genesis 26:7) claimed that their their wives were their sisters.

- Levirate marriage, where man marries the childless widow of his brother in order to provide an inheritance, record in both Genesis 38:8 and the Mosaic law, is recorded in the Nuzi tablets.

- The practice of a nomad returning to his family to find a wife for his son is recorded in the Mari tablets.

- It was possible to sell one's birthright to a younger brother.

- In Genesis 25:23, the Hebrew term for the eldest son is not the usual one, but based on an Akkadian word which is found in the Nuzi tablets and others of the same period, but not later.

- In Genesis 35:22, Reuben's adultery with his father's concubine caused him to lose his inheritance rights as firstborn. In the tablets and law codes, a son could only be denied his inheritance rights by serious offences against the family.

- The adoption of Ephraim and Manasseh by their grandfather in Genesis 48:5 is comparable with a similar adoption at Ugarit, using a standard adoption formula.

- The gift of a female slave as a dowry is seen in the Nuzi tablets and Babylonian law codes. The authority over any children who arose from that slave-girl belonged to the main wife.

- Certain oral statements were accompanied by recognised rituals which functioned as legal safeguards. These might include placing the hand under the thigh, and the correct placement of the right hand.

None of this proves that Abraham, Isaac and Jacob existed, but it is not intended to. Nor does it help fix their date. The various customs described persisted for a long time, throughout the second millennium. Nor is it intended to suggest that everyone in the ancient world adopted these customs and practices. But these correspondences between the Biblical account and the various customs and laws found in Mari, Nuzi and Babylonia do answer the question of whether the general picture of the society that existed at the time that the stories are set. The sceptic would prefer it if they didn't, as it would make his task easier. But instead we find that there are numerous parallels suggesting that the Patriarchs acted in the same way as some other people of their general time period and culture. So this particular line of attack against their historicity is foiled.

Camels, Philistines and other "Anachronisms"

But, of course, there are also claims that some things in the Genesis account don't match what is known about the culture of the time. The two most commonly cited were those raised by Professors Finkelstein and Silberman, as discussed above. The Biblical text mentions domesticated camels in various places, but camel bones aren't found in Israel before the tenth century. And the Genesis text mentioned the Philistines, but the first reference to them outside the Bible are in various inscriptions by Ramesses III, as part of an invading force, at a much latter date.

Camels

The reason why Professor Finkelstein and others have a problem with camels is that the earliest evidence of camel domestication found in Israel and the surrounding area are various camel bones found in an archaeological dig and dating (according to the conventional chronology) to around the tenth century -- the time of David and Solomon. Obviously, this is much later (a thousand years later on the early chronology) than the time of Abraham.

This is an argument from silence, and not a very good one at that. Archaeological investigations will only find evidence of camel domestication from people who owned camels and lived among the settled population, in towns or cities. Nomads or traders passing through the land would not leave behind evidence, or at least we would not expect them to. The Genesis texts state that camels were owned by:

- Abraham and his family. A great many of which were acquired by Abraham during the time he spent in Egypt. Abraham's family in Haran also seemed to be familiar with camels, but there is no indication that they owned them. However, it is likely that some of Abraham's camel herd might have originated in Mesopotamia.

- The Ishmaelite and Midianite caravaneers, who sold Joseph into slavery.

- Since Abraham obtained many of his camels from Egypt, the Egyptians would have needed to have domesticated the camel at this time.

It does not state that camels were owned or used by the native Canaanites. And there is no obvious reason why the Canaanites would own camels. Camels are used as beasts of burdens, particularly when crossing a dry or desert country. Camel hair and milk are also used by nomadic populations in the desert, but not so much by more settled populations who have better alternatives. If you are living in a town in Israel, which can be a dry country but is no desert, there is no obvious reason why you would need a camel. So it would not contradict the Biblical text if archaeology showed that the Canaanites owned no camels, which is the best that it can do. And the archaeology does not even show that. Very little evidence survives to our day. If a small number of Canaanites owned camels, particularly if they dwelt outside the main towns and cities, that still does not mean that we would have found camel bones in the limited excavations that have been carried out.

Bactrian Camels were first domesticated at about 3000BC by the cultures that lived around the Caspian sea. The practice seemed to be picked up by Mesopotamian cultures and the domendary camel during the third millennium, and then spread into Egypt. We do not possess much evidence of camel domestication -- we have little evidence at all of anything from that time -- but there are a few examples.

For example, this small statue of a kneeling camel dates from the time of first dynasty of Egypt

From the Egyptian old kingdom (about 2200 BC), we have an image carved on a rock showing a man leading a camel

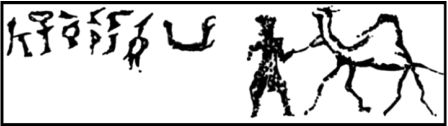

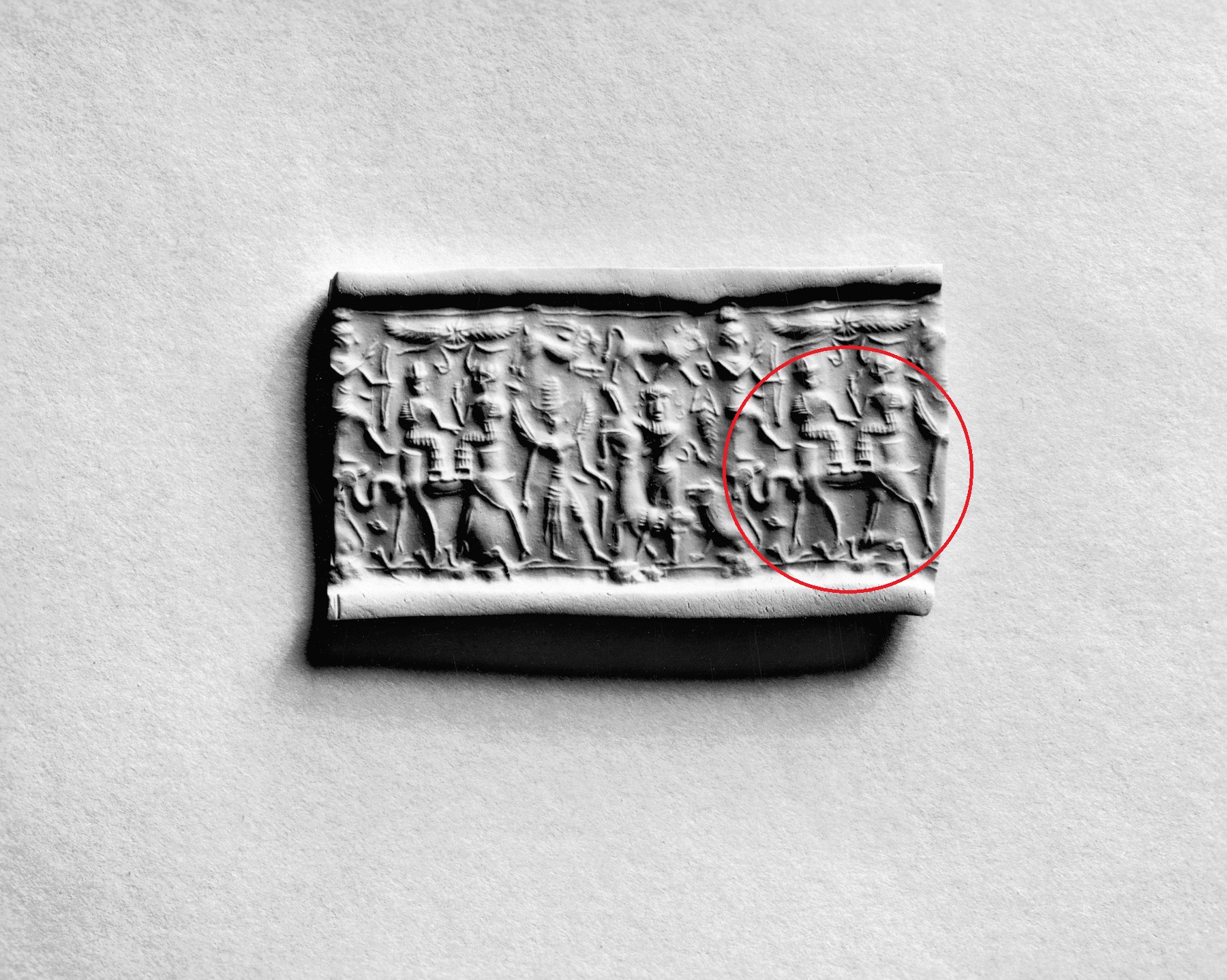

At about 1800BC, slightly after the time of Abraham by the Chronology I favour, and about the time of Abraham on others, we have this cylinder seal found in Syria, which depicts two people riding a camel.

There is this statue of a Bactrian camel from Mesopotamia from around 2000BC. Note the rope around the neck of the camel, indicating that it is domesticated.

Camel bones and hair from the third millennium BC ave been found in tombs in Jericho and Arad. We have various texts suggesting camel domestication from the early 2nd millennium BC, around the time of the Patriarchs.

I have taken these images and data from an article by Titus Kennedy, which goes into far more detail. In short, we have clear evidence of the domestication of camels in various parts of the ancient Near East, including in Egypt and Syria where Abraham obtained his camels, before and during the time of the Patriarchs. There is no reason to view the references to camels in Genesis through to Joshua as anachronistic.

Philistines

The other anachronism that is frequently raised regards the Philistines. The Philistines, Israel's main rivals for the latter part of the judges era and up until David's time, are known from Egyptian records. At the end of the Late Bronze Age, there was a collapse of much of Near-Eastern civilisation. The Hittites disappeared as a major power almost overnight. Various Syrian cities, including the important city of Ugarit, were destroyed. We find destruction layers in numerous cities down the Eastern Mediterranean coast. Records we have speak of invaders coming in ships and ransacking and destroying everything. These are known today as the "Sea peoples." The wave of destruction spread south, and reached the borders of Egypt. There Pharaoh Ramesses III, the last great Egyptian New Kingdom Pharaoh, won a battle against the Sea Peoples, saving Egypt from the same fate of the Hittites (although the New Kingdom would disintegrate soon afterwards, due to internal pressures and division). Ramesses III describes the enemy in the inscription at Medinet Habu,

The foreign countries (i.e. Sea Peoples) made a conspiracy in their islands. All at once the lands were removed and scattered in the fray. No land could stand before their arms: from Hatti, Qode, Carchemish, Arzawa and Alashiya on, being cut off (i.e. destroyed) at one time. A camp was set up in Amurru. They desolated its people, and its land was like that which has never come into being. They were coming forward toward Egypt, while the flame was prepared before them. Their confederation was the Peleset, Tjeker, Shekelesh, Denyen and Weshesh, lands united. They laid their hands upon the land as far as the circuit of the earth, their hearts confident and trusting: 'Our plans will succeed!'

The name transliterated from the Egyptian as "Peleset" is equivalent to the Hebrew term transliterated as Philistine. They are mentioned in subsequent Egyptian texts, showing that they settled in the land. In the early chronology, it was also at about this time that the Book of Judges starts to record significant Philistine oppression of Israel.

The question, then, is if the Philistines arrived in the 12th century BC, as attested in Egyptian and Syrian inscriptions, then how could Abraham and Isaac have had dealings with them in the much earlier Middle Bronze Age?

Firstly, I should discuss how the Bible agrees with this narrative. As stated, the Biblical account in Judges does record that the Philistines increased dramatically in strength at about the same time as the sea people attack, in Judges 10. Before this, they are mentioned only sporadically. After it, they become Israel's chief enemies. Secondly, the Biblical account clearly records that the Philistines were foreigners. They were not of the same stock as the Semitic people who dominated the area. There is a strong biblical tradition that the Philistines came from the Islands around Greece.

For example, in the table of nations, we read (all Biblical quotations from the ESV),

Genesis 10:13 Egypt fathered Ludim, Anamim, Lehabim, Naphtuhim, 14 Pathrusim, Casluhim (from whom the Philistines came), and Caphtorim.

This is repeated in 1 Chronicles 1. Later texts ascribe the Philistines to The Caphtorim,

Deuteronomy 2:38. As for the Avvim, who lived in villages as far as Gaza, the Caphtorim, who came from Caphtor, destroyed them and settled in their place.

Jeremiah 47:4 Because of the day that is coming to destroy all the Philistines, to cut off from Tyre and Sidon every helper that remains. For the Lord is destroying the Philistines, the remnant of the coastland of Caphtor.

Amos 9:7 "Are you not like the Cushites to me, O people of Israel?" declares the Lord. "Did I not bring up Israel from the land of Egypt, and the Philistines from Caphtor and the Syrians from Kir?"

The location of Caphtor and Casluhim is not completely clear, but there is a firm consensus, based on references to those lands in inscriptions from Mari and Ugarit, that it refers to somewhere in the region of either Crete, or the Aegean Islands, or maybe mainland Greece. That part of the world. This agrees well with the depiction of the Philistines at Medinet Habu, who wear armour and helmets in a style known from Minoan artefacts found in Crete.

So to the Biblical authors, the Philistines were a people from the area of Greece, who settled in Israel or the surrounding lands. This leads us to the question about whether earlier Greek colonists would also have been termed as Philistines, either by the original Biblical authors, or by some copyist later on updating the text. Could it be possible that Moses originally wrote Abimelech the Caphtorim, and the later scribe changed this to Abimelech the Philistine?

So do we have any evidence that the Minoans settled in the area of Philistia before the sea peoples?

Abimelech dwelt in Gerar, which is frequently identified with Tell-Haror. This was the largest city in the region in the MB2b period, and the site had links with Minoan culture. For example, there is a graffiti on a shard of Pottery that originated in Crete, and and other Cretan pottery found in the MB2 city. If Gerar was in fact a nearby city (as I have proposed), that doesn't change the observation that there were (at a later time) Minoans in the local area.

Likewise the harbours along Canaanite coast, which were established by the early MB2 period period, show clear signs of interaction with Crete and the general Aegan area, for example in pottery, the architecture of the harbours which show Minoan influences, and various plant seeds of a species which is native to Crete and the Aegean, but not the Middle East. This plant was considered a delicacy to the Minoans, but needs to be carefully prepared, a skill which the Canaanites would not have. In the North of Israel, at Tel Kabri, there is a palace decorated with Minoan frescos, indicating that some Minoans at least had settled there. Of course, this is no evidence that there were Philistines ruling Gerar, but it does suggest that at least some Minoans of the time period were willing to settle down in the coastal areas of Canaan. They might have gradually adopted the pottery and way of life of the locals, while still maintaining a distinct ethnic identity and national mythology. These, the argument goes, would have been the Philistines of Abraham's day.

We thus have clear evidence of contact between the Minoan culture and the coast of Canaan in the MB2 period, and perhaps the last stages of MB1. Almost certainly some Minoans settled down in Canaan as a consequence of those links.

None of this is clear evidence that the Minoans established colonies in coastal Southern Canaan in late MB1 and early MB2, which is what we would need to reconcile with the Biblical mention of Philistines. Neither do they demonstrate that the Philistines dominated MB2b Tell Haror or MB2a Tell Beit Mirsam, or wherever we want to place Biblical Gerar. However, nor does the evidence rule out the idea that there was an earlier wave of Caphtorim settling in the area that would later become known as Philistia in early MB2. There is clear evidence of trading links between Crete and the Canaanite coast at that time, so the idea that there was a Minoan presence in South Western Canaan at the time of Abraham is plausible.